Anton Szandor LaVey, born Howard Stanton Levey in 1930, remains one of the most controversial figures in modern religious history. Best known as the founder of the Church of Satan and author of The Satanic Bible, LaVey has been described both as a brilliant philosopher and as a dangerous provocateur. What makes his story even more intriguing is the influence of his Jewish background and how it has been connected with his unique brand of “moralist Satanism.”

LaVey was born into a family with Jewish roots, and his original surname, Levey, is often associated with Jewish heritage. While he never practiced Judaism in a traditional sense, the cultural influence of Jewish history, storytelling, and identity shaped how he viewed religion and morality. Judaism has always carried a strong tradition of questioning authority, debating scripture, and exploring the complexities of human behavior. These themes would later appear in LaVey’s Satanic philosophy, though presented in a radically different way.

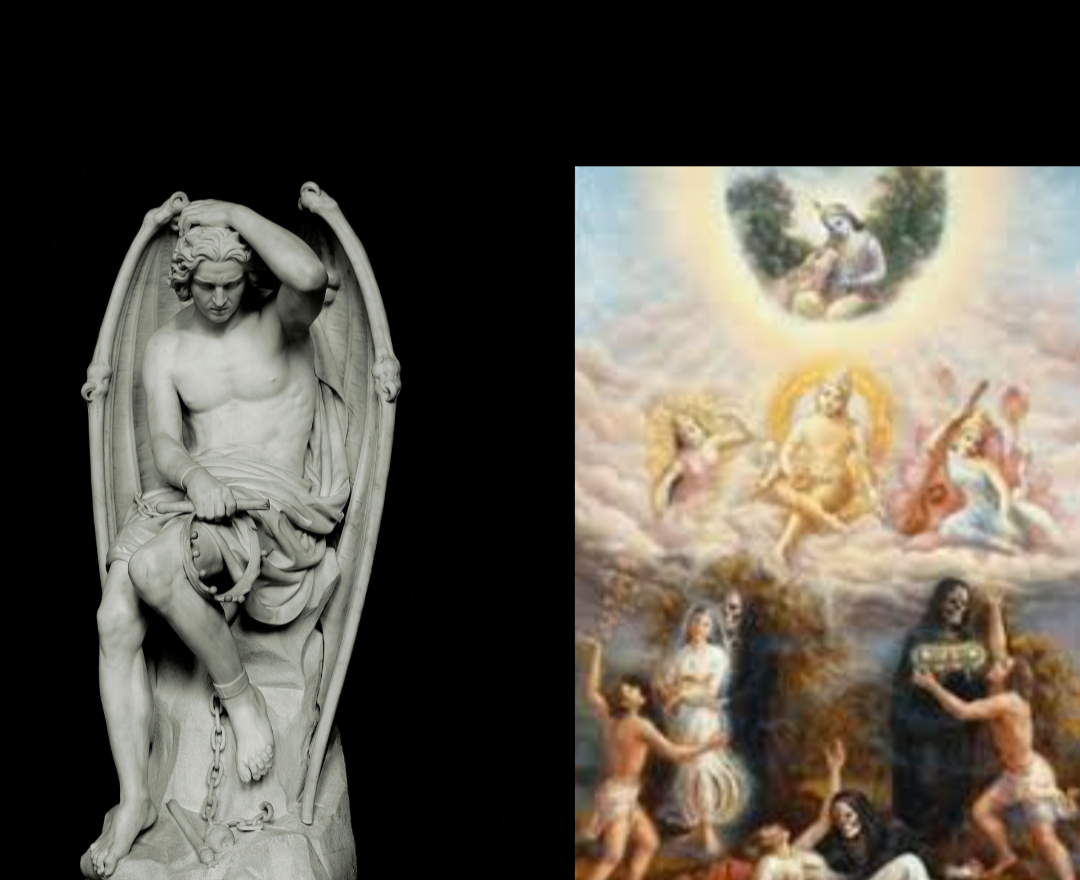

Critics often labeled LaVey a “devil worshipper,” but he rejected the idea of Satan as a literal being. Instead, he used Satan as a symbol of rebellion, pride, and human nature. This symbolic use mirrors aspects of Jewish cultural thinking, where the “adversary” (the Hebrew ha-satan) was not an independent god of evil, but an opposing force — a challenger meant to test and provoke. LaVey’s reinterpretation of Satan aligned with this ancient concept, though he gave it a theatrical, modern twist designed to shock a Christian-dominated society.

The Jewish cultural background also played a role in his emphasis on ethics and responsibility. While LaVey rejected traditional commandments, he embraced a type of moral realism — a “moralist Satanism” that encouraged individuals to live honestly, accept human desires, and reject hypocrisy. His message was not to descend into chaos, but to face life without illusions. In this way, his teachings reflect a cultural heritage rooted in critical thought and resilience, transformed into an entirely new belief system.

Anton LaVey’s life continues to stir debate because it challenges mainstream narratives about religion, culture, and morality. His Jewish heritage, blended with his dramatic embrace of Satan as a symbol, created a philosophy that was part cultural critique, part performance, and part spiritual rebellion. Whether one views him as a visionary or a deceiver, LaVey forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about faith, freedom, and the power of cultural identity.